My mother hovers in and out of my bedroom while I’m dressing. At breakfast I get this letter:

Dear Miss Tate,

Phyllis tells me you are going to Bramlands tomorrow. I shall walk over from Newtimber after luncheon, reaching Bramlands at about 2.15, as I want particularly to speak to you.

Yours very sincerely, Charles S. Buxton

I am surprised and much annoyed….

I arrive home in rain. I arrange 3 p.m. for Charlie Buxton. I’m still terribly miserable at the thought of an ordeal like this. I eat a nondescript meal.

Sunday. I arrange to send the cart for my singing mistress (Fannie Wood), who has been ill, to bring her to tea at 4 today. Somebody had to be collected or how am I to get rid of that boy, when I want?

I come to the conclusion that it’s the duty of mothers to insist on girls doing things for their own happiness and pleasure and not from a sense of duty, or because by doing things they please other people. I am thankful firstly to Joan because she first encouraged me to be selfish and do things to please myself and not other people. John’s nurse did too. And finally you. Four, three or two years ago if this had happened I should have thought, ‘Oh well it seems it will make him very happy. I may as well marry Charlie Buxton, I like him all right.’ Result? Who can tell? It might have been all right or it might not.

3.20. He came and we went for a walk along the lane, making careful conversation about everyday affairs.

Then: ‘Tate, is it any good, do you think you could care for me?’

‘I’m so dreadfully sorry. I wish you wouldn’t go on. I’m afraid I don’t.’ I feel I would walk into hell with alacrity to avoid this interview.

‘Don’t you think you ever could? It would help me so much and I’m sure,’ with rather a defiant jerk of his head in a proud way, ‘I’m sure you could make something of me.’

I prod holes in the mud with my stick, not knowing what words would be least brutal.

Then I say, ‘I’ve always liked you and looked on you as just a relation of Phyllis’; not much point in that remark but I’m quite as miserable as he is. He wore no hat, red bow tie, and primroses in his button hole.

‘Is it any good my trying again?’

Involuntarily I cry beseechingly ‘Oh! not again soon.’

He, very gravely, ‘No not soon.’

Again I say, ‘I’m dreadfully sorry but I really don’t care, and I can’t help it, can I?’ With a ghastly smile he says, ‘Well, will you shake hands?’

‘Oh yes,’ very relieved that it really has come to an end! Then solemnly we shake hands and two miserably wretched eyes through spectacles burn themselves on to my brain in a way I shan’t forget quickly. We say ‘Goodbye’ and I return along that lane, covered with twigs and leaves and hard flints, my head bowed and viciously hitting every leaf I can with my stick.

I write to my mother and say that the boy has gone, ending with, ‘I’m so awfully sorry he should be so miserable. I am not like the rest of your daughters who have a readiness to fall in love with great rapidity!’

A few days later I received a wire from Miss Robins in Germany saying, ‘Good girl’, which cheered me and I burned a joss stick in celebration, as I felt I had her thoughts to comfort me.

….

On 9 June I had another letter from Charlie. By the grace of God I met the postman so that my family knew nothing about it. He returned to the charge and asked me if there was still no hope.

I spent hours that night trying to write a firm but not unkind reply and finally sent it to Miss Robins to read and send on if she felt I had adequately covered the ground.

The constant harrowing at home was having the effect of turning me in upon myself, making my roots go deeper, helping me to grow up. I was constantly subjected to remarks on why did I not wish to marry Charlie Buxton. It became unbearable and got on my nerves. I lost weight largely through being unable to eat my meals without fear of arguments. I worked myself up to a frantic degree in an outburst to Miss Robins in the following letter:

9 June 1911

When I was eighteen I would have married anything that might have asked me if I thought it would have been advantageous and conducive to fun. Didn’t believe in any silly rot like love and I might have been the most amenable daughter alive. From that time onwards I never thought about the matter from a personal point of view.

When that letter came in London I was most awfully sorry and wished I had never seen the boy. I was perfectly miserable and from trying to imagine how he felt I almost felt I was a criminal. I didn’t think about myself at all except in a dull way I knew it was utterly impossible. When he came and I walked along the lane with him I felt I was a beast and quite dreadfully sorry. But when he spoke of it, though he said quite nice things, I suddenly felt so revolted at what it all meant from my point of view. I was so staggered at the horror of such thoughts that (I didn’t tell you this before) to prevent the sleeve of his coat touching mine I walked in the ditch! If I have ever grown up it was at that moment. Anyhow I suddenly saw a great many things horribly realistically and it completely took my breath away. And among other things I felt I was on the same level as an animal.

But if he had gone on to say any more than he did I could have picked up the stones from the road and hurled them at him. As it was I pulled myself together, tried to summon some of the sorryness I had felt before for him, but which had suddenly died and shrunk to nothing, and I behaved fairly decently. But I was really absolutely dazed and felt I had come up against something too horrible for words and which I could not understand. And that awful look. Ugh! The sort of greedy way a particularly greedy old mutual acquaintance eyes the strawberry dish, a craving for possession. No, I’m not going to think about that any more or it will get on my nerves again. Only I did want you to understand a little. Well, after a little while I covered up and tried to ignore the fact that I had ever opened my eyes for a moment. Sometimes I was successful, sometimes not. What simply dug itself into my mind was the beauty of friendship. When I could think of that, and of you, I was a little consoled.

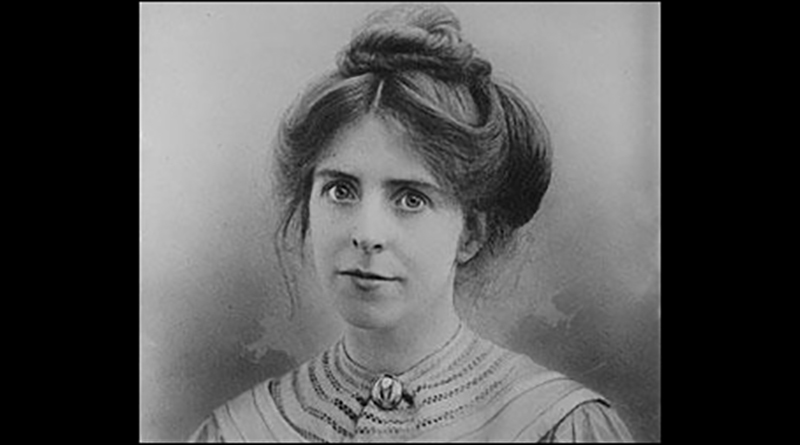

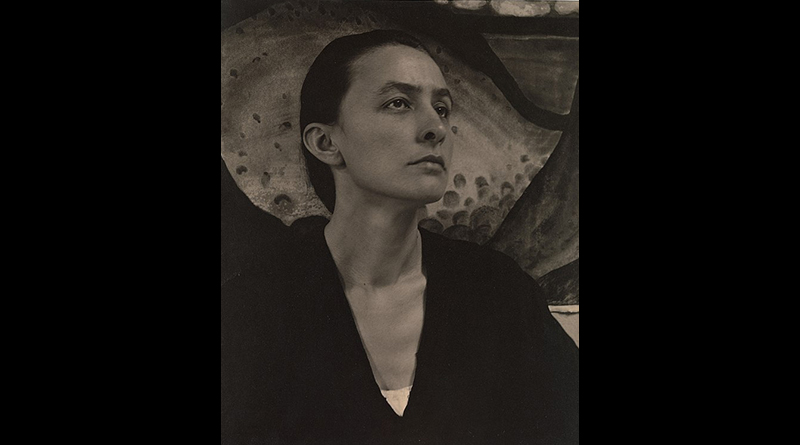

— Octavia Wilberforce, in her book Octavia Wilberforce: The Autobiography of a Pioneer Woman Doctor