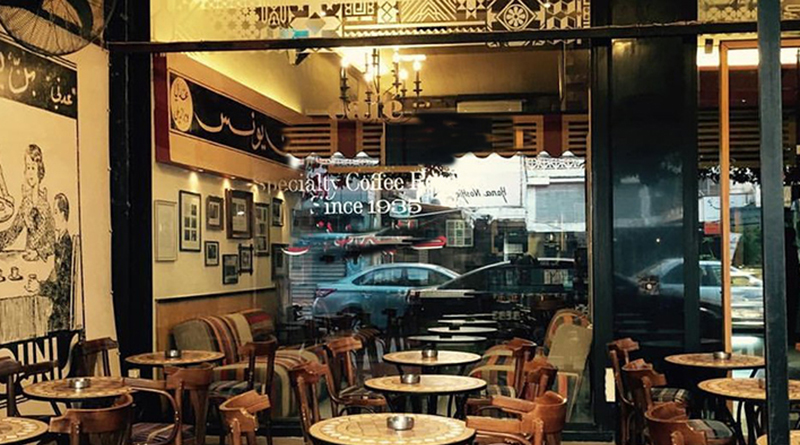

It was just a coffee shop with half a dozen customers, none of whom seemed to even glance up at my arrival. I took a seat in a small booth with my back to the wall. This meant I could keep an eye on the parking lot and see who drove up. I had not watched all those spy movies for nothing.

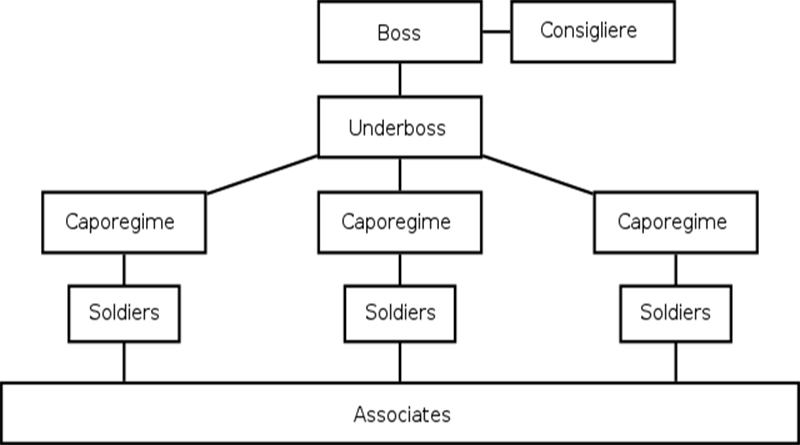

While I was keeping my vigilant eyes open for anything untoward, someone sat down beside me. I mean, this guy with a brown leather briefcase just materialized out of nowhere, set the briefcase under the table, and sat down beside me. He was not an Arab. Not his skin, not his hair, not his accent. He was an American. It wasn’t Terpil — I had seen Terpil’s picture before coming to Beirut — but he claimed to be Terpil’s “associate.” No name, just an “associate.”

“Why do you want to meet Frank?” This confirmed that he was not an Arab. If he were, we’d have blown the first twenty minutes on polite chatter over cups of sugary tea.

“Because there are stories written about him in the States,” I answered, “and I want to ask him if they’re true.”

“How do I know you’re who you say you are and not working for the government?” This guy cut to the quick.

“Because I brought a picture. Take it, fax it to your associates in the United States, ask them if I’m a correspondent for ABC News, or not.”

Of course that wouldn’t really prove anything. There have been cases over the years of overtly legitimate journalists covertly feeding information to the U.S. government. Those who did so hurt the credibility of those who did not. But my offer seemed to convince the guy that I was who I said I was.

“Tell me what you want to ask Frank. Maybe I can answer some of your questions, and if you’ve still got more, maybe you can talk to Frank.” And that’s about as far as we got. Just as quickly as my contact had appeared out of nowhere, two more guys did the same. But they didn’t sit down at the table. They towered over it.

My tablemate started shaking. Not a single word from our visitors, but he seemed to know who they were and why they were there, and he was shaking, and starting to mutter, and then squeal, “No, not me, no, not me, nooo …”

It didn’t really seem like a party where I wanted to stay. But it didn’t seem like I could just get up and leave, either.

It felt like they stood there for a minute or so, just staring down at this guy next to me. But there was a message in their eyes: “Come peacefully, or not. Up to you.”

Not.

I don’t think the shaking man at my side actually made some kind of conscious decision to hold his ground. I think he was just too scared to move. So they moved first. These two thugs reached over the table, each grabbing this guy under one arm, and pulled him across. Coffee cups and cream and sugar bowls went flying, but hey, the owner can always buy more.

My contact wasn’t just squealing anymore, he was screaming. “Noo, nooo, pleeeese, noooo, nooooo, noooooo!”

Three things flew through my mind: 1) Live by the sword, die by the sword; 2) Maybe instead of journalism school, I should have gone to law school; 3) I was really glad I never learned the guy’s name.

Now let me tell you what happened with our eyes: mine never met his. The abductors were bad guys, but he was too, and I didn’t want any part of his problem.

And their eyes never met mine. They were about as interested in me as they were in the porcelain now shattered on the floor. Thank goodness!

The other customers, veterans of life in Beirut, never looked up. Well, maybe once, but then they quickly resumed the appearance of non-involvement that had kept them alive so far through all the years of Lebanon’s civil war.

That was the last time I saw the guy who sent me a message to meet him at the Alexander. The last time I even heard about him. His abductors had to drag him, kicking uselessly, all the way to a car. My hearing’s not so hot, but I could hear him screaming ’til they slammed the door on their way out. I don’t suppose he screamed much longer.

That might have been the end of it. But I couldn’t be sure. Some mysterious American arms dealer had just been dragged kicking and screaming from a hotel coffee shop by a couple of mysterious Arab thugs, and I was the other guy at the table. Worse still, he had left the briefcase. — Greg Dobbs, in his book Life in the Wrong Lane: Why Journalists Go In When Everyone Else Wants Out (read for free)