Stieglitz brought Georgia to the bright little studio apartment of his niece, Elizabeth, who was living elsewhere. When Georgia had arrived in New York, she was tired and ill. Stieglitz ordered her to stay in bed, and had his brother, a well-known doctor, examine her. Stieglitz himself visited every day, and even learned how to boil eggs for her. He returned to his apartment after his wife was asleep. Within a week he was writing to Arthur Dove of Georgia’s “uncommon beauty, spontaneity, clearness of mind and feeling, and the marvelous intensity with which she lived every moment.” A month after her arrival, they had become lovers and Stieglitz was also living in the studio at 114 East Fifty-ninth Street, a blanket modestly hung between their sleeping quarters.

The fifty-four-year-old Stieglitz brought his young love to his family’s summer compound at Lake George. The family was astonished at the change in the dour Stieglitz.

Some found it sweet that they headed for a row on the lake every evening after dinner; others complained that it was disgusting that their holding hands on the porch led them soon to more intricate convolutions and suddenly to a mad dash into the house. In my day, seven years later, an occasional exchange of winks could trigger Georgia’s blouse-unbuttoning sprint up the stairs and Alfred’s laughing pursuit — and the red-faced elders’ rush into conversation to stifle Peggy’s and my childish questions.

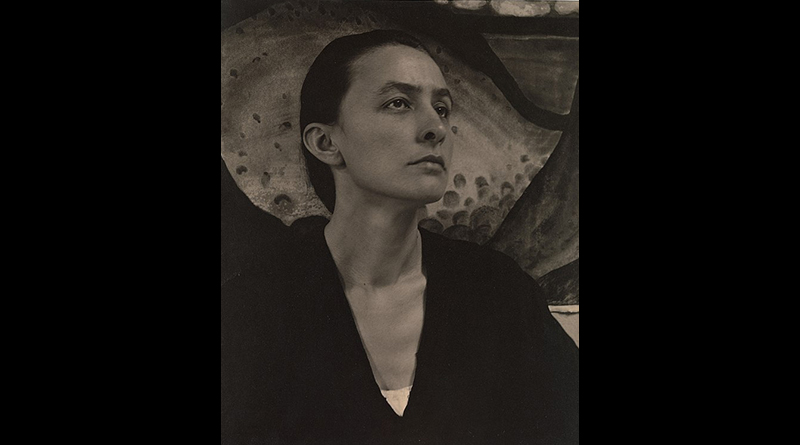

As she painted he photographed.

Alfred’s eye became insatiable, feasting on the slender but voluptuous contours of his love. The need to photograph her became exigent; the studio skylight made it possible at almost any time. Georgia’s every mood and every gesture — sultry or virginal, gay or sullen, teasing or angry, drowsy or blazingly alert, quizzical or amused, clothed, nude, tousled or coiffed — propelled him to the camera. He choreographed her hands — stitching domestically, at rest, sometimes seeming to soar, sometimes lifting her breasts like twin offerings (a pose that, with almost comic predictability, he later instructed nearly all his nude subjects to assume). He sat her in a chair, propped her on pillows in the bed, stood her on the low radiator, leaned her against a table. His “portrait” of her became a love song with a new melody to record every day.

A niece from Lake George remembers meeting her for the first time.

Rehearsed by grandmother Lizzie, and with all the concentration of a not-quite-three-year-old, I offered my hand, performed my curtsy, and pronounced on cue, “How do you do, Aunt Georgia?” — to which her instantaneous response was a cheek-stinging slap and a blazing “Don’t, ever, call me Aunt!”

— Sue Davidson Lowe, in her book Stieglitz: A Memoir/Biography (read for free)