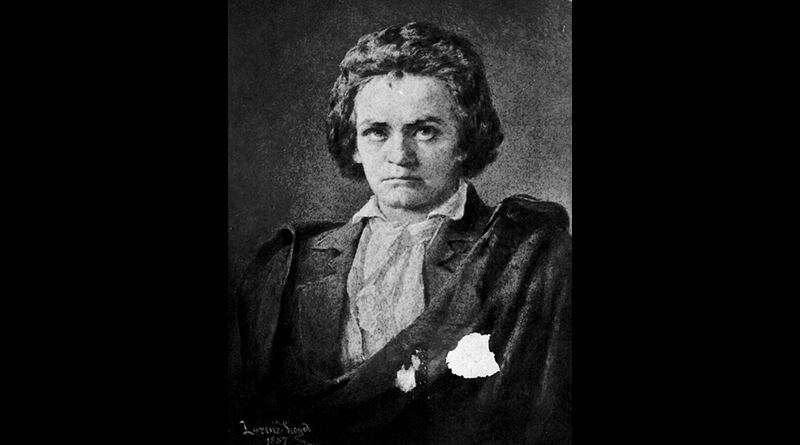

One or two years later I was living with my parents during the summer in the village of Heiligenstadt, near Vienna. Our dwelling fronted on the garden and Beethoven had rented the rooms facing the street. Both set of apartments were connected by a hall in common which led to the stairs. My brothers and I took little heed of the odd man who in the meanwhile had grown more robust, and went about dressed in a most negligent, indeed even slovenly way, when he shot past us with a growl. My mother, however, a passionate lover of music, allowed herself to be carried away, now and again, when she heard him playing the piano, and entering the connecting hall would stand, not beside his door, but immediately beside our own in order to listen with devout attention. This she may have done a couple of times when suddenly Beethoven’s door flew open, he himself stepped out, saw my mother, hurried back and at once rushed down the stairs into the open, hat on head. From that moment he never again touched his piano. In vain my mother, since every other opportunity was lacking, had a servant assure him that not alone would she no longer eavesdrop on his playing, but that our door leading to the hall should remain locked, and her household, in place of the stairs in common, would make a broad detour and use only the garden entrance. Beethoven remained inflexible and his piano stood untouched until finally the late autumn brought us back to town again.

During one of the summers which followed I made frequent visits to my grandmother, who had a country house in the adjacent village of Döbling. Beethoven, too, was living in Döbling at the time. Opposite my grandmother’s windows stood the dilapidated house of a peasant named Flohberger, notorious for his profligate life. Besides his nasty house, Flohberger also possessed a pretty daughter, Lise, who had none too good a reputation. Beethoven seemed to take a great interest in this girl. I can still see him, striding up the Hirschgasse, his white handkerchief dragging along the ground in his right hand, stopping at Flohberger’s courtyard gate, within which the giddy fair, standing on a hay- or manure-cart, would lustily wield her fork amid incessant laughter. I never noticed that Beethoven spoke to her. He would merely stand there in silence, looking in, until at last the girl, whose taste ran more to peasant lads, roused his wrath either with some scornful word or by obstinately ignoring him. Then he would whip off with a swift turn yet would not neglect, however, to stop again at the gate of the court the next time. Indeed, his interest was so great that when the girl’s father was put in the village lock-up (known as the Kotter) for assault and battery while drinking, Beethoven personally interceded for his release before the village elders assembled. But as was his habit, he handled the worthy counsellors in so tempestuous a manner that he came near keeping his captive protégé company against his will. — Franz Grillparzer, quoted in Beethoven: Impressions by His Contemporaries, edited by Oscar Sonneck (read for free)