Complaining alternately of light-headedness or chest pains, I visited the ER more often than most people see their GPs (probably more than most people see their parents). Incidentally, besides my socialism, my hypochondria is one of the reasons I never complain about kicking in tax dollars to pay for universal health care; I’ve had cardio stress tests that turned out to be for little more than my undershirt being on backwards.

This firmament of generalized worrying has, over the years, been punctuated by more acute bouts of panic….

…To walk away from a dizzying ex nihilo crying jag without any curiosity about why it happened seems something like saying, “Well, that was unpleasant — let’s hope that next time I eat shellfish, my throat doesn’t inflate like a Zeppelin!” before digging into another surf and turf. Instead, the panic attack that finally forced me into addressing them as an ongoing medical problem took place in just the place where you’d expect an inveterate leftist to be driven to the brink of hysteria in those pre-Naheed Nenshi and pre-Rachel Notley days: Alberta.

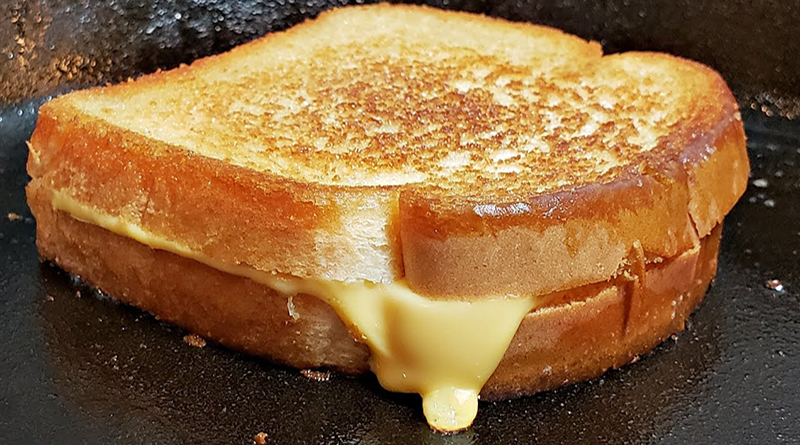

I was on the road as a touring opening act stand-up comedian for the first time in my life and had spent several days in the sort of personal health-related panic I had become an expert at over the years. Over the course of my days, I have alternated between periods of being what you might call pretty fat and what you might call very fat, and this was during a very fat phase. Standing in a sports bar in Lethbridge, where we were supposed to do a show despite the fact it was NHL playoff season, I felt a pain in my left arm (in retrospect, probably it was just my soul trying to escape from my body). I became convinced I was having heart problems. A day or two later, I found myself in a hotel room in Calgary in the middle of the night, suffering from what appeared to be a heart attack. All the signs were there: my arm felt funny, my chest hurt, my pulse was racing and I had pizza sauce all over my face.

Now, there are several reasons why one might find oneself having a heart attack in Calgary. Perhaps you’re David Suzuki, or a vegan, or a bull. But I am none of these things, so I decided I had to get to the emergency room, where I could get on with the business of dying. Riding to the hospital, I kept stealing glances at the taxi driver, who was a moustachioed ginger — and although this should have comforted me, as it made him a composite of what my redheaded mom and French-Canadian dad looked like when I was a kid, it didn’t. Instead, I kept thinking, This is the last person I’ll ever see. This is the person with whom I end my life. It didn’t even make me feel better knowing that, by dying, I’d get out of paying the fare.

Inside the hospital, I placed terrified phone calls from the waiting area to my brand-new wife, trying desperately to telegraph my love and hysterical terror through the payphone, across the Rockies. Lying on a bed inside the ER, I plumbed new depths of fear, facing down eternity with even less confidence than I had taken to the stage earlier that week after contracting to do significantly more time than I had material to cover, before crowds who could generously be described as indifferent. I stared up at the ceiling of the hospital, plunging into more fear than I had the resources to deal with, so I turned to humanity’s oldest circuit breaker: for the first time in my adult life, retrieving the religious language of my Anglican upbringing, I prayed. Like the solipsist in every myopic faux-damascene conversion story, I prayed hypocritically to a God I hoped would forgive me for my until-that-very-second atheism and spare my life. I begged Him to save me. And a few seconds later, a nurse wheeled an EKG machine into my area, hooked me up to it in what seemed like one fluid motion, told me I was perfectly fine, then disconnected the machine and disappeared. After that, a doctor explained I had had a panic attack. By the time I left, I’d been acquainted with two of humanity’s great soothers of the soul: prayer and Ativan.

Invariably, relief follows the discovery that one has had a panic attack rather than a heart attack — even though the phrase “panic attack” is made up of two profoundly terrifying words, whereas the phrase “heart attack” is only one terrifying word, qualified by one of the most comforting words in the English language. So on paper, panic attacks are worse. But heart attacks can kill you; panic attacks — as horrifying as they are — cannot. For this reason, the initial response to finding out you have panic attacks is often relief — followed by disappointment at the realization that, although you get to live, you may be doing so with chest pains, dizziness and diarrhea. But in my view, panic sufferers needn’t view themselves as shaky, shitty people. Instead, we should see ourselves for what we are: paragons of evolution, the ultimate culmination of Darwinian natural selection, in all of its horror and brutality.

Just as twenty-first-century toddlers with access to corn syrup are weighing in at three hundred pounds because Cro-Magnon man had a hard time finding sugar and fat, the problem of panic is a physiological one rooted in the differing circumstances between us and our remote caveperson ancestors. As much as they make one feel like a weenie, the symptoms of panic attack each bear evolutionary advantages related to the fight-or-flight instinct, also known as the Air Canada Imperative. When faced with a sabre-toothed tiger or a she-wolf, our hunting-gathering ancestors generally had two options: they could stand and fight, or they could run away. These vestigial instincts are still apparent in human behaviour today. When you respond to stress by acting like an asshole, that’s fight. When you respond by acting like a coward, that’s flight. When you write something mean in an internet comments section, you’re doing both.

Fight-or-flight was a crucial survival system, yet it has bequeathed us both anxiety disorders and panic attacks—the symptoms of which usually correspond to an evolutionary survival mechanism.

Let’s take an easy and relatable one to start: excessive sweating. Those suffering from panic will often begin to sweat profusely and disgustingly. But according to the website for AnxietyBC, a West Coast mental health resource website (meaning it’s just like the mental health resource websites in Toronto but less ambitious or career-focused), the evolutionary advantages to profuse sweating are obvious: “Sweating cools the body. It also makes the skin more slippery and difficult for an attacking animal or person to grab hold of you.” Incidentally, we may just have stumbled upon the very worst superpower of all time.

Panic attacks often involve rapid heartbeats and a constriction of the chest — but these are merely fight tactics, with blood being pumped to the major muscle groups and chest muscles tensing for battle. Chest pains, sweat, heavy breathing — these are the hallmarks of a warrior, and that’s why there’s nothing scarier than a sixty-year-old businessman who’s just had to take the stairs instead of the escalator.

The list goes on—panic sufferers often feel a sense of reality seeming less real, also known as the Tea Party effect. Again, according to AnxietyBC, this is because of the dilation of the pupils to let in more light. Sexual and gastrointestinal dysfunction come from the body de-emphasizing non- essential systems in a time of crisis, which to my mind raises the question: What exactly do we mean by non-essential? That said, if you’re being chased by a bear, it’s probably better not to have an erection — not only will it be easier to run, but you’ll seem like a smaller meal.

— Charles Demers, in his book The Horrors: An A to Z of Funny Thoughts on Awful Things