Madeleine Béjart’s faith in her young lover was still unshaken, but Paris would have none of them ; so the undaunted pair went forth to seek their fortune in the provinces. The temptation to return to his father’s house must have been very strong, but Molière’s belief in himself was still the confidence of youth, the glow in the heart that lessens only with the years.

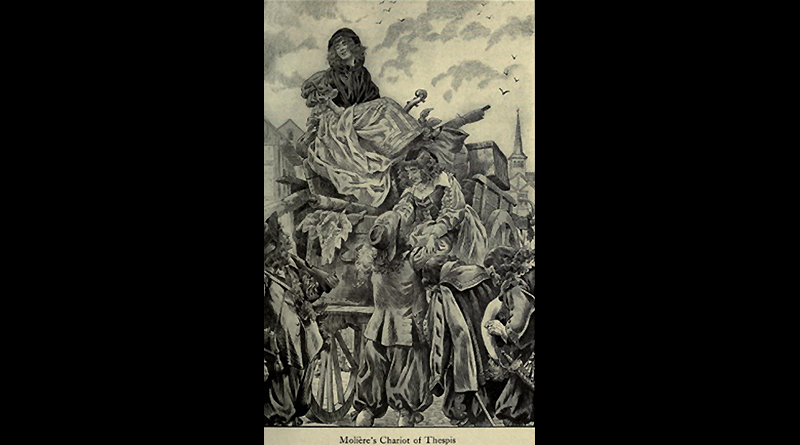

When Molière fled from Paris, he became, in the phrase of the theatre, a “barn-stormer.” An ox- cart was his home, his play-house some vacant grange or tennis-court. Eventually he obtained a following in certain towns, and recognition as an official entertainer in at least two provinces ; yet for nearly thirteen years he was at best a vagabond, tramping the highroads of France beside his unwinged chariot. Court records, the registration of infants born to his actresses, and entries in a few provincial ledgers of payments made to his company are the only recorded facts relating to the first eight years of his wanderings ; so in order that the story may be told at all, it becomes necessary to shed a dim light of circumstantial evidence upon that darkest period of his life. Only the Béjarts Madeleine, Joseph, and Geneviève are known to have accompanied him in his flight from Paris, and he was of so little importance, even in the theatrical world, that no record of his departure has been preserved.

…It is far easier to believe that he fled to the provinces shortly after his second escape from prison than that he was able to dodge both bailiffs and gaolers from August thirteenth, 1645, to December twenty-fourth, 1646.

… Of far more human interest, however, than the date of his departure for the provinces is the fact that he had the pluck to persevere in his chosen calling. Overwhelmed by discouragement and disgraced by a debtor’s cell, his most natural course would have been to re-enact the story of the prodigal’s return ; but rather than acknowledge defeat, he became an outcast denied even the right of Christian burial. In those days the strolling player was beset by want and persecution, while the unsettled state of French politics added the danger of highway robbery to the certainty of police oppression. Courage and perseverance are qualities which distinguish genius from mere cleverness, and when Molière turned his back upon the joys of Paris to lead a life of privation and social ostracism, he proved the quality of his fibre.

The best existing picture of life in a travelling theatrical company, at the time when Molière took to the highroads of France, is in Scarron’s Comic Romance (Le Roman comique), a story of the trials, tribulations, and amours of a band of strolling players, told with true picaresque humour and gaiety. It was evidently inspired by some travelling company which the worldly abbé met while attending the general chapter of St. Julien at Le Mans in 1646, and as Molière and La Béjart bear a vague resemblance to the hero and heroine, more than one attempt has been made to prove that he had them particularly in mind. But other theatrical companies were tramping the highroads at the time, and M. Chardon, who has studied the matter exhaustively, comes to the conclusion that Molière was not the hero. The opening paragraph of Scarron’s story might pass, however, for a picture of Madeleine Béjart and her young lover at the time they were forced to storm the barns of provincial France:

Between fi�ve and six in the afternoon a van entered the market-place of Le Mans. It was drawn by four lean oxen led by a brood mare, whose colt scampered back and forth about the vehicle like the little fool it was. The bags, trunks, and long rolls of painted cloth which �lled the chariot formed a sort of pyramid upon the apex of which sat a young girl whose country garments were relieved by a touch of city �nery. A young man, poor in dress but rich in countenance, tramped beside the van. . . . Upon his shoulder he carried a blunderbuss which had served to assassinate a number of magpies, jays, and crows. These made him a cross-belt, from which a chicken and a gosling, evidently captured in desultory warfare, hung by the legs.

This ox-cart described by Scarron was typical of Molière’s own chariot of Thespis. When it halted at the end of a day’s journey, village urchins greeted it with jeers ; and while the footsore actors who had tramped behind its creaking wheels argued with some swaggering archer of police for permission to set up their trestles, village rakes with feathered hats against their breasts besieged the tired actresses, sitting huddled on its pile of baggage, with offers of gallantry and ribald compliment.

The strolling player found manifold trials awaiting him on every hand ; bandits infested the highroads, the police were merely authorised brigands, and so great was the prejudice against his calling in certain localities that a tatterdemalion mob armed with stones sometimes greeted him at the end of a day’s journey. Even in more hospitable regions, he was forced to seek an official permit to present his comedies, and for some vacant grange or tennis-court to serve him for a play-house. A few deals laid upon wooden trestles were the veritable “boards” he trod ; and as his theatre was frequently a barn, the term “barn-stormer” is no misnomer. If his company were affluent, it might boast a roll or two of canvas daubed to represent a street or palace ; but his scenery was more likely to be merely a pair of travel-stained curtains which rumpled the hair of his tragedy queen as she made her haughty entrance. His lights were only tallow dips stuck by their own grease on a pair of crossed laths ; his orchestra, a drum, a trumpet, and a pair of squeaking fiddles ; while in costuming and “make-up” he did not attempt historical accuracy ; a tawdry toga and a plumed helmet sufficed for the classic heroes of both Greece and Rome; a clown’s dress or swashbuckler’s cloak for comedy parts. For the buffoon, he whitened his face with flour and pencilled grotesque moustaches on his lips with charcoal ; but nature herself was usually the “make-up artist.”

An official permit obtained and his theatre ready, the manager of a strolling company must then secure an audience. This was no simple matter. His drum-beats gathered a crowd ; and by an harangue on the marvels of his actors he endeavoured to extract sufficient coppers from the pockets of his yokel auditors to keep out of the bailiff’s hands. To feed a dozen mouths when five sous was the price of admission was a task to appal even the most aspiring heart.

— H.C. Chatfield-Taylor, in his book Molière, an Autobiography