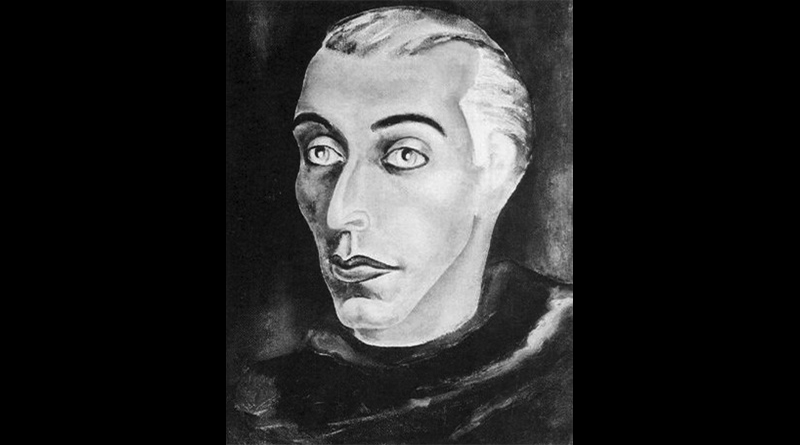

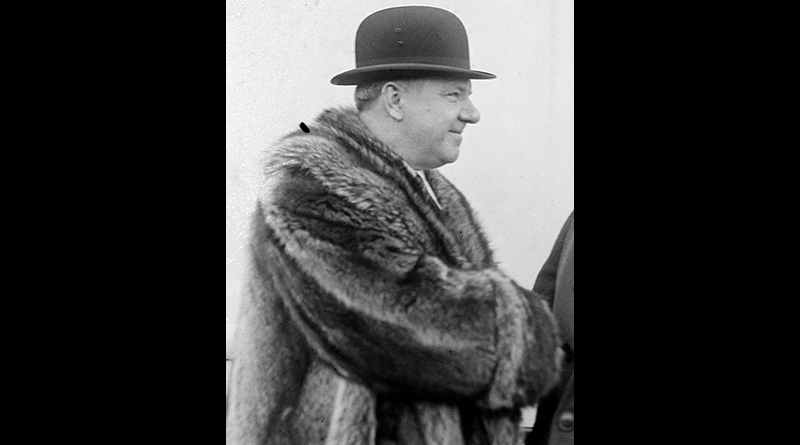

After I separated from the air force in 1971, I kept flying airplanes — off and on — and reading about flying. I finally bought a 1946 Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser in 1989. I named her Annabelle. She was beautiful — a red and white fabric-covered, old-fashioned, nose-high “taildragger.” I have never been more attached to a possession. Just after my maiden flight in Annabelle, I read the most technically elegant book I’ve ever read, a book penned in 1944: Stick and Rudder: An Explanation of the Art of Flying, by Wolfgang Langewiesche.

And then in 1991, after two years of flying all over North Carolina, down to Mississippi, up to D.C., I reached the end of my honeymoon. I crashed Annabelle. She was totaled, but nobody was hurt. I crashed not because of Stick and Rudder, but in spite of it. In fact. Stick and Rudder helped save my life, but before I say how, I want you to know more about this technical book — this little work of art.

Most books about flying airplanes start something like this: “The primary objective of this chapter is to demonstrate to the reader the theory of flight through an overview of the four basic forces of flight: lift, drag, weight, and thrust.” A detailed analysis of each force follows. The prose is dry, non-personal. Langewiesche begins: “Get rid at the outset of the idea that the airplane is only an air-going sort of automobile. It isn’t. It may sound like one and smell like one, and it may have been interior-decorated to look like one: but the difference is — it goes on wings. And a wing is an odd thing, strangely behaved, hard to understand, tricky to handle.” The language is refreshing, suspenseful, and accurate. After his opening paragraph, Langewiesche explains how a wing flies. But he doesn’t explain à la air force technique — by way of Bernoulli’s Theorem. He says, “When you studied theory of flight in ground school, you were probably taught a good deal of fancy stuff concerning an airplane’s wing and just how it creates lift. Perhaps you remember Bernoulli’s Theorem: how the air, in shooting around the long way over the top of the wing, has to speed up, and how in speeding up it drops some of its pressure, and how it hence exerts a suction on the top surface of the wing. Forget it…. The main fact of all heavier-than-air flight is this: The wing keeps the airplane up by pushing the air down…. Trying to understand the piloting of airplanes by concentrating on Bernoulli … is like trying to catch on to tennis by studying just exactly how the rubber molecules behave in a tennis ball … instead of simply observing that it bounces!”

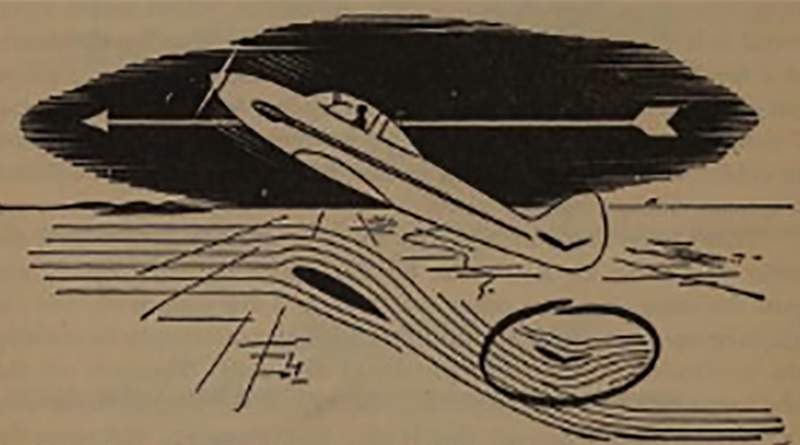

Langewiesche goes on to explain angle of attack (the angle at which the wing meets the air). The wing is like a hand out the window of a fast-moving car. The hand, level, goes neither up nor down. But move the front of your hand upward slightly (thus creating a “positive angle of attack”) and you see how, at this positive angle of attack, your hand meets the air and washes it down, thus creating lift. Your hand moves up….

… Ah-ha. The book was teaching me about writing, showing me how fancy, strange concepts can be made plain by a writer who is able to write clearly and simply — about technical stuff — by using relationships and sensations familiar to most of us. And not in a belittling or reductionist way. Stick and Rudder‘s clever use of metaphor and lively, active sentences that sound like talk helped Mr. Langewiesche do something he hadn’t planned. As he went about explaining the art of flying and in the process making the unfamiliar familiar, he inspired me to be a better writer.

The crash. I crashed because I was stupid and because I was smart. The stupid part is this: I chose a bad day to fly. The wind was from the wrong direction and I took off with a high wind to my back. A no-no. Unfortunately, the short, grass runway was downhill and takeoffs were allowed in only the downhill direction (after starting the take-off roll around a dogleg). The smart part was that after becoming airborne, I immediately put the aircraft back on the ground, straight ahead. I put it down on the remaining runway, rolled into a field, hit a ditch, and flipped Annabelle over onto her top. I put it back down because I felt that if I continued I might not make it over a line of trees ahead in the distance. I put it down straight ahead because of all that had been eloquently (and at length) preached and demonstrated to me in Stick and Rudder: Don’t attempt low, slow turns.

Langewiesche’s re-creation of sensation through clarity, simplicity, and sensible use of language had helped me get into my bones, while reading, what had been in my head about the extreme danger of low, slow flying.

I haven’t flown an airplane since the crash. But I plan to. In the meantime. Stick and Rudder: An Explanation of the Art of Flying remains close at hand. And when I get lonesome for some flying, I start reading. On any page. It puts me in the air.

— Clyde Edgerton, in his essay “The Most Technically Elegant Book I Read,” from the book Remarkable Reads: 34 Writers and Their Adventures in Reading, edited by J. Peder Zane