By this time [1906] the new factory was built and new machinery had been put inside it, and one day in January, a little before my thirteenth birthday, we went to see it. Mario took us round, and as I was standing with a mass of loose curling hair almost to my knees, the wind of a steel shaft caught it. I was snatched up, revolving, with my head ground against the shaft and my feet floating horizontal. I know that it seemed a very long time: at each revolution my feet struck a wall or pillar and I wondered if my shoes were coming off. I felt no pain or even fright. Then Mario wrenched me out and carried me away; I saw terrified faces; heard the machinery coming to a standstill; felt a warmth trickling down my neck; saw my mother meeting me with panic in her eyes that I noticed even at that moment; and next I was on mattresses in the office and some doctor was sewing my eyelid into place. Half the scalp was torn away. After a few days an ambulance came to take me to Turin, wrapped up, with the snow lying all about us. My mother stayed with me all the time.

In Turin we went to a famous grim old man who had a nursing home. Its snowy gardens, with never a soul in them, already looked like a cemetery: I got very little nursing or attention: they operated, grafting pieces of somebody’s skin, and it failed: and I was gradually dying. Then a young doctor from Dronero spoke to the chief surgeon of the general hospital in the middle of the town; against all medical etiquette, he said he would take me; the nursing home let me go thinking they meant to carry me to England: but my mother saw me across Turin and put me into a private room in the hospital. The young doctor invented a new scheme: they grafted my own skin from the thigh on to the scalp and covered it with net, so that the dressings could be done through it without disturbing the new application, and it took. This is probably a commonplace now, but it was new at the time. The dressings of my flayed legs were more agony than any physical pain I have ever had to suffer: but I healed slowly, and had four months to grow accustomed to the hospital routine.

The head surgeon was a tiny little man, almost misshapen, with a deep sing-song Ligurian voice. He was the son of a peasant and a sort of saint, loved by everyone who came near him — his whole life given to his patients. He used to come walking round the hospital every morning, very stiff and small under his big head, like a Byzantine Primitive, and show me off as a remarkable object to an obsequious circle of students. The nuns fluttered around him with the wings of their headdresses like doves; you had only to step an inch or two out of their straight line of vision to be unseen if you happened to wish to be so, and perhaps that is why these coifs were invented. I began to enjoy my life again. All sorts of people sent presents — among others a Japanese doll I was fond of, whose head the young doctor used to pull out of its socket and tell me that its anatomy was wrong and I was too old for dolls: but I have never grown too old for childish things.

I can still feel the warmth and delight of my mother’s presence. She now devoted herself to me and I discovered her as it were. Her love, which now became greater for me than for Vera, probably dates from this time when I was nearly lost. After about two months my father arrived, and sat for hours at my bedside, showing his affection by rubbing my arm gently, till he chafed it raw: I was too polite to ask him to stop, and perhaps dimly conscious that it made him happy to think he was doing something for me.

The hospital looked out on a public garden and trams. It is a mistake to think that invalids like privacy all the time: I used to watch the gardens from a balcony and get interested in the dramas I could follow there day by day, an uninvolved watching of other lives I still think one of the best of entertainments.

When the spring came I began to be driven out or to seek in the parks of Turin some patch of ground to be on, and smell the grass growing and feel the earth again, as if life itself were pouring back through the living season. My head was bandaged; and when I got tired my father carried me with a struggle of tenderness that he could not express. The words “underneath are the everlasting arms” make me think of those spring days whenever I come across them….

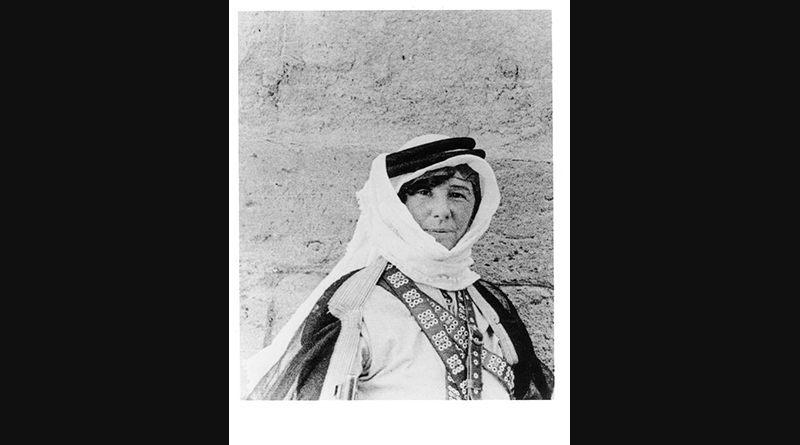

Four months in a hospital are very long, and we returned to Dronero at last. I wore white lacy caps to cover my cropped and torn head. The scars got much smaller, but have always remained, and were a constant trouble, making me self-conscious, and also no doubt spoiling such looks as I might have had. The only other damage was that for several years I could not see even a sewing-machine wheel turning without feeling a little sick. — Freya Stark, in the first volume of her autobiographies, Traveller’s Prelude (read for free)