First things first: as a chicken rancher, you do not need a rooster in order for the hens to lay eggs. Hens lay eggs nearly daily for most of the year, in accordance with the length of the day (i.e. waxing in spring and waning in winter). The only thing a rooster can do that is useful to humans is to fertilize the eggs if you’d like to have chicks. Fertilized eggs have no more nutrients than unfertilized eggs.

Notice that I wrote the only “useful” thing. Just about everything else a rooster does is completely obnoxious. They crow — not just in the morning but any old time. Sometimes all night. And it’s not necessarily a quaint “cock-a-doodle-doo” it might sound more like someone is strangling the poor creature, which you will be inclined to do before long.

There’s a reason words like “bantam” and “cocky” have the meanings they do — roosters are chock-full of testosterone. A rooster’s idea of foreplay is dancing around in a circle with one wing dragging on the ground. That’s not so bad — so why are the ladies running away? Because then the rooster chases down a female and jumps on her, pushes her into the dirt, pins her head down with his beak (usually pulling a couple of feathers for effect), tries to keep his balance for a few seconds, and then hops off.

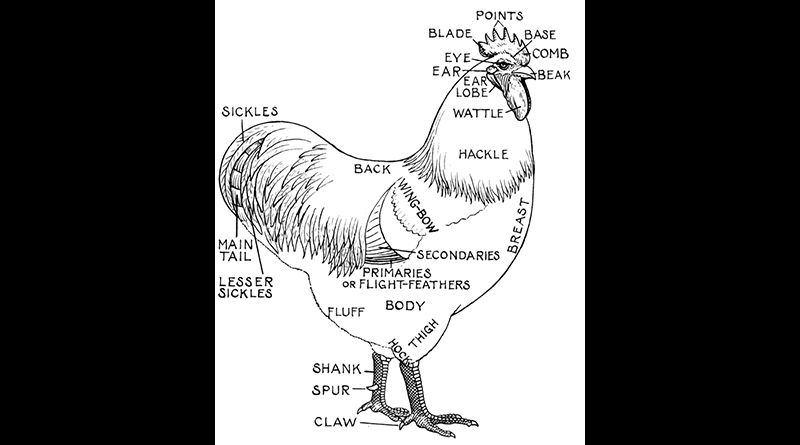

Their other charming quality which, to be fair, is understandable and rather noble, is to protect the eggs. Guess who wants to come in and take the eggs? You. They may attack with both their beaks and with their spurs, sharp protrusions that grow on their legs. I know people who have had their clothes torn by an attacking rooster. One friend enters her chicken yard with a large walking stick to keep her rooster — a bantam no less — off of her. Never let a rooster near a small child.

The first batch of chicks I bought had two males, which I butchered after they started demonstrating their skills at about five months. A few years later, well-meaning friends brought us two chicks as a gift (Note: LIVE ANIMALS ARE NEVER A GOOD GIFT), and of course one grew into a male. I tried to give Mr. Man a chance. Maybe I overreacted last time, I thought. Maybe he won’t be so bad since he started out so much younger than the hens. When he started crowing, it was entertaining — sort of like a teenage boy whose voice is changing and cracks at inopportune moments. He had amazingly beautiful feathers — males grow more showy feathers around their necks and big tail feathers that arc up over their rumps. He grew tall and proud. He was afraid of me and of the hens on the high end of the pecking order. See, I told myself, this will all work out.

And then Mr. Man got randy. I started noticing feathers in the yard (no one was molting). I started noticing that the chickens were hiding in the hen house during the day instead of being in the yard. And then Mr. Man started mounting chickens, even upper-caste ladies, right in front of me. I tried to convince myself that I was projecting my human ideas of healthy sexual relations on the chickens, because what was going on in the henhouse sure looked like rape. I tried to be open-minded. Maybe the hens like the sense that someone is in charge, I thought.

The day that I made up my mind, I was mulching garden beds. I heard a commotion. I had coaxed the lowest-rung chickens out of the henhouse to forage (they’d been hiding there all day), and now, they were all yelling and clucking. I looked up to see Mr. Man in hot pursuit of Billy Sue. Those chickens can run fast when they want to! He chased her in circles, unrelenting, until she ran under the deck and started beating herself against a window in the basement wall in an attempt to get away from him. Billy Sue did not look like she was in any way complicit in the proceedings. Mr. Man ended up in the freezer.

I have read heart-warming accounts of roosters standing guard over “their” hens; protecting them from predators and pointing out food to them. Maybe after puberty, which Mr. Man did not survive.

I’ve considered the argument that what is going on in there is “natural.” But when it comes down to it, almost nothing a chicken is or does is “natural.” Humans have made chickens (and to a lesser extent other domesticated farm animals) what they are, over centuries of selective breeding. Do you know of any other bird that lays an egg each day? — Kristy Athens, from her book Get Your Pitchfork On!: The Real Dirt on Country Living (read for free)